By Graeme Bassett

The Day of the Clone is exciting and intriguing when viewed objectively now. Those of us old enough to have seen the original broadcast, and who have forgotten what happened, find ourselves unable to predict how it will all end.

Those of us watching Timeslip more than 50 years since that first showing also have a sense of coming through the other side of the Barrier; Liz and Simon, once our elders, are now much younger than we are. When they mention a year, our fingers twitch involuntarily as our brains tally how many decades ago that was.

The years have hopefully provided a chance to come to terms with the fear of age and decay which permeates Bruce Stewart’s three earlier stories and is brought to the boil by Victor Pemberton in The Day of the Clone.

Pemberton, following on from The Year of the Burn Up, brings Simon and Liz back to their present of 1970. Fearing for Liz’s safety (and perhaps a bit jealous) her father splits the pair up, sending Simon home to his father. We experience a brief mood of end-of-school-holiday depression, feeling that the adventure is over and dull reality has reasserted itself. But then Liz disappears and her parents must turn to Simon to find her.

Pemberton, following on from The Year of the Burn Up, brings Simon and Liz back to their present of 1970. Fearing for Liz’s safety (and perhaps a bit jealous) her father splits the pair up, sending Simon home to his father. We experience a brief mood of end-of-school-holiday depression, feeling that the adventure is over and dull reality has reasserted itself. But then Liz disappears and her parents must turn to Simon to find her.

Where the previous two stories had futuristic science-fiction settings, Day of the Clone has more in common with the TV show The Avengers. Simon reasons that Commander Traynor is involved in Liz’s kidnapping and follows her trail from present-day Whitehall to a secluded country house with hi-tech trappings. One that turns out – in an outrageous piece of conversational sleight-of-hand – to be round the corner from St Oswald and the time barrier.

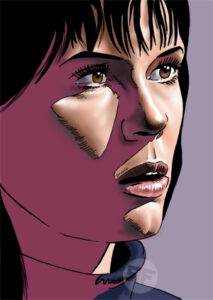

Simon breaks into the house and encounters Maria (Mary Larkin), one of several elderly patients undergoing some kind of therapy in the building.

Maria, a new character, is the equivalent in story terms of Beth who was the future-self of Liz in the previous two adventures. But whereas Beth was a projection of how Liz might turn out, Maria is a key to how it all started. When Simon and Liz escape through the Barrier into 1965, they meet a version of Maria much younger than a mere backtrack of five years would suggest…

Maria, a new character, is the equivalent in story terms of Beth who was the future-self of Liz in the previous two adventures. But whereas Beth was a projection of how Liz might turn out, Maria is a key to how it all started. When Simon and Liz escape through the Barrier into 1965, they meet a version of Maria much younger than a mere backtrack of five years would suggest…

Simon’s encounters with Maria have an eerie power despite the challenges of making a young actress up to impersonate a geriatric in the 1970 sequences. There are slight overtones of Philippa Pearce’s 1958 novel Tom’s Midnight Garden, with two different ages in two different time zones. Pearce’s novel had been adapted by the BBC’s Merry-Go-Round programme in 1968 and, like Timeslip, drew upon the theories in JW Dunne’s book An Experiment With Time. But where the girl in Pearce’s novel ages over a natural span, Maria’s life span is compressed horrifically.

Liz and Simon, once back in 1965, also encounter a younger version of Commander Traynor as well as Morgan Devereaux who was last seen in the future of The Time of the Ice Box. And Pemberton cunningly reverses the balance of power between the two men.

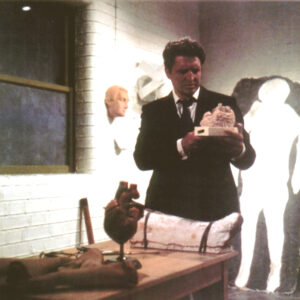

Aided by Ian Fairbairn’s Dr Frazer (the original human model for the clone Alpha 4 in 1990’s Burn Up – cleverly indicated purely by quick visual flashbacks to Fairbairn in Burn Up and with no explanatory dialogue), Devereaux resists Traynor’s attempts to cancel his early experiments in life-span longevity and cloning development. Traynor is imprisoned secretly and replaced by a clone duplicate at some point.

Denis Quilley (Traynor) and John Barron (Devereaux) deliver a theatrical super-charge to this final story. Their characters could have fallen into caricature easily at this stage, but their energetic performances are never less than convincing.

Denis Quilley (Traynor) and John Barron (Devereaux) deliver a theatrical super-charge to this final story. Their characters could have fallen into caricature easily at this stage, but their energetic performances are never less than convincing.

There is a hint of a scientific explanation for the Barrier as Liz and Simon discover that Devereaux has set up time chambers in the country house. His young guinea pigs are dressed in period costumes, hypnotised and subjected to soundwaves that help them regress to a different historical period, tying in with the theory that Simon and Liz never actually travel in time which is why they can’t be harmed physically in their adventures.

The story ends, somewhat inexplicably, in 1970, with the real Traynor released from captivity by Simon and Liz (or ultimately, Liz’s mother Jean) with Traynor confronting his clone and telling him: “You don’t exist.”

Liz and Simon had encountered the clone of Devereaux as “a projection” in a possible future. But Traynor’s replacement had been from his own time. Or had it? How had Frazer and Devereaux and their team managed to grow a fully matured clone to replace Traynor back in 1965? There’s a mention of 103 skin grafts and hypnotic conditioning apparently as part of the process but that would all take time.

Did they hypnotise Traynor to do Devereaux’s bidding and replace him only later? Or had Devereaux’s time chambers somehow brought the clone back from the future? If the clone Traynor was contemporary, did his sudden shocking knowledge of his true origins unleash some poltergeist energy in that final showdown at the barrier?

Although the producers insisted that the series had come to the right end of time, Victor Pemberton couldn’t resist a tantalising hint of future adventures when he had Liz ask the real Traynor if the clone was gone. “Until you meet him again some day – on the other side of the Barrier,” Denis Quilley crinkles. “Well, it is possible. Isn’t it?”