By Richard Farrell

After a trip back in time to World War Two, the second Timeslip story sees Liz and Simon propelled forward into a possible future. It builds on the technological advances hinted at in the first story and takes them to a quite sinister conclusion.

As something of a newbie to Timeslip (I have vague memories of only the first two stories in the 1970s, the shocking fate of Dr Joynton never forgotten), I’ve found a lot to commend in this serial.

There are certain aspects which I appreciate now more than I would have done as a youngster though the story succeeds in working on a number of levels. Part of its appeal is its mature approach to the effect of scientific advancement on the individual and the way it questions whether the price of progress may be too high in some cases.

Keeping the Skinners central to the story adds an essential feeling of involvement for the viewer; the story moves at a good pace with gripping revelations in each episode which gradually reveal the fate of Liz’s family in this version of 1990.

This future world depicts a society reliant on technology, where scientists strive for perfection and the advancement of science – but at a terrible cost as we shall see. Liz’s family is cocooned in this isolated, automated world (known as the Ice Box) and as the story gradually unfolds we see the effect this technological world – which promotes the reliance on intellect at the expense of emotion – would have on both her and her parents.

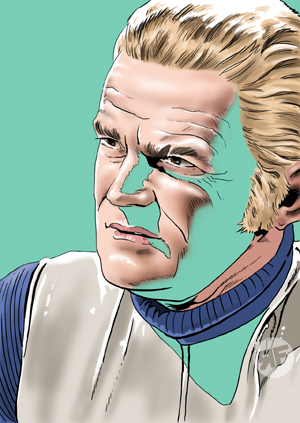

This sterile outpost is controlled by Morgan C Devereaux (played by John Barron), the scientist behind a string of inventions including the longevity drug which has the benefit of prolonging people’s natural lifespans. So if you’re taking HA57 and are planning to live past 100, you’d better top up that pension pot.

This sterile outpost is controlled by Morgan C Devereaux (played by John Barron), the scientist behind a string of inventions including the longevity drug which has the benefit of prolonging people’s natural lifespans. So if you’re taking HA57 and are planning to live past 100, you’d better top up that pension pot.

The Antarctic setting for this story is apposite as it is a fitting metaphor for Beth (with Mary Preston playing this future version of Liz) and Devereaux, the base controller who she follows so blindly: it’s isolated and very, very cold. The proposed AB Experiment – the replacement of healthy limbs and organs – further underlines the dehumanising effect of this advanced society on people.

In some ways this six-parter shares DNA with Kubrick’s epic 2001: A Space Odyssey. Both depict people living in a world where they have become reliant on technology – Bowman and Poole aboard Discovery and Floyd aboard the Spacewheel and Clavius Base; without their sophisticated tools they could not survive in their new environment, space.

While 2001 has its protagonists Floyd and Poole separated from their families on significant days – birthdays in both cases – Timeslip has Liz’s future family together in the Ice Box but they remain emotionally distant due in part to the results of Beth’s intelligence enhancement course (which on the face of it seems to have given her a sense of humour bypass at the same time).

She is now committed to intellect at the expense of her feelings – this is underscored by her less-than-engaged reaction to her own father’s fate in the Ice Box.

As in Kubrick’s film, the supposedly infallible computer makes an error which has widespread ramifications.

The Ice Box’s computer incorrectly assumes Simon and Liz are the volunteers for the AB experiment and later, due to a fault inherent in Devereaux himself, causes a shockingly unexpected and horrific result in proceedings.

The Ice Box’s computer incorrectly assumes Simon and Liz are the volunteers for the AB experiment and later, due to a fault inherent in Devereaux himself, causes a shockingly unexpected and horrific result in proceedings.

The central character in the Ice Box is the super-logical Devereaux. He is “a man of the future” – he may be superior intellectually but emotionally he is very much lacking. His inflexibility and intolerance of mistakes leads him to attempt to apportion the blame for a death on one character (Larry), then another (Bukov), and eventually having to face the unacceptable conclusion. He is, in effect, the glitch in this system.

Dr Joynton (Peggy Thorpe-Bates) is the counterpoint to Beth and Devereaux, being the institute’s mother figure and an identification figure for the young audience. She is the warmest person Simon and Liz find in the Ice Box (more so than Liz’s own mother); she looks after the pair and takes an interest in their well-being. It is significant that she becomes the first victim when the technology fouls up in this computer-controlled world.

Simon, our young scientist of the year, returns to the Ice Box after being pressed by the sinister Traynor to steal scientific information. I wasn’t entirely convinced by his motivation myself, but as Simon did have ambitions in this area it’s just about acceptable, though did he not realise that giving the Traynor of 1970 details of the longevity drug could change his own future, possibly for the worse?

Beth, so very different in temperament to young Liz, is remote from all the others on the base, rejecting Larry’s interest in her and following Devereaux blindly.

She finally learns that her total trust in the latter and the computer is misplaced as the systems on the base fail with catastrophic results. The final shot of her hand in Larry’s suggests that, albeit late in the day, she has rejected Devereaux’s way and rediscovered her true feelings.

Projecting the future in film or TV can throw up some interesting ideas, especially when viewed in retrospect. Timeslip’s relatively serious approach to science bears fruit with surprising accuracy. I was impressed that the Ice Box staff have access to all TV channels and can print off any newspaper of their choosing – it looks like someone invented the internet and iPlayer a few decades early!

Projecting the future in film or TV can throw up some interesting ideas, especially when viewed in retrospect. Timeslip’s relatively serious approach to science bears fruit with surprising accuracy. I was impressed that the Ice Box staff have access to all TV channels and can print off any newspaper of their choosing – it looks like someone invented the internet and iPlayer a few decades early!

Anyone familiar with Gerry Anderson’s UFO would recognise the repurposed Century 21 consoles in the control room and Devereaux’s secret back room. Waste not, want not! It’s also notable that silver was the de rigueur colour used to denote “the future” in ‘70s telly. It’s a familiar aspect of Timeslip and its contemporaries and adds to the series’ retro-futuristic appeal.

The bright blue and yellow accents on the costumes indicate a bold design aesthetic – colour was new to British TV in 1970 and if you’ve got it, why not flaunt it. It’s just a shame that this explosion of design flair can only be experienced in one extant colour episode.

The theme of scientific progress was common in other speculative fiction in film and TV at the time and Timeslip riffs on the same ideas, a reaction perhaps to Harold Wilson’s “white heat of technology” which blazed a fiery trail through the 1960s.

2001 warned of the need for the human race to remain master of its tools and more than one episode of Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet alerted young audiences to the perils of full automation.

The Space: 1999 episode Missing Link is also worth a mention as, like this story, it suggests that it’s just as important to feel as to think, to balance the two sides of human nature – something that eventually dawns on Beth.

This projection of 1990 is a world in the grip of the advancement of science for its own sake and it’s shown to have a detrimental effect on the family; Devereaux’s ultimate failure underscores that perfection is in fact not achievable. Nor desirable.