By Paul Mount

The 1960s saw an explosion of creativity in television. The public began to look ever more towards the box in the corner and the new pioneers of entertainment began to explore its potential.

The success of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass serials on the BBC in the 1950s (and his controversial adaptation of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four) led to more science-fiction series and serials such as 1961’s A For Andromeda and its 1962 sequel The Andromeda Breakthrough. The early 1960s also saw shows including ITV’s Pathfinders trilogy targeting a younger audience. The success of Doctor Who and the growing confidence shown by Gerry Anderson as his puppet shows became more ambitious prompted a huge investment in “genre” entertainment; notably from ITC in the UK in their lavish adventure series and in the US with sci-fi anthology shows like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, juvenile high-concept series such as Lost in Space and Land of the Giants, and the legendary Star Trek.

Time travel was exploited in many of these shows; Doctor Who’s “An Adventure in Space and Time” brief survived through the 1960s, the crew of Star Trek’s Starship Enterprise popped up in various eras of history and Irwin Allen’s The Time Tunnel presented two scientists adrift in Time.

But most of these shows handled the concept of time travel superficially by some convenient bit of sci-fi mumbo-jumbo. It fell to a modestly-budgeted British series for children at the start of the 1970s, a decade that would be grittier, grimmer and greyer than the sparkling and optimistic 1960s, to offer a rationale for the fanciful idea of bouncing around in Time. Timeslip changed everything, even if it’s rarely recognised as having done so.

Timeslip was a revolution in British children’s television, a series so popular with its audience that it grew organically into a 26-part serial whose themes and ideas danced and dovetailed across its run, touching upon then-obscure real-world concerns such as cloning, global warming and Artificial Intelligence. And it all began with a family on holiday in the sleepy village of St Oswald…

Timeslip was a revolution in British children’s television, a series so popular with its audience that it grew organically into a 26-part serial whose themes and ideas danced and dovetailed across its run, touching upon then-obscure real-world concerns such as cloning, global warming and Artificial Intelligence. And it all began with a family on holiday in the sleepy village of St Oswald…

The six episodes of The Wrong End of Time (WEOT), beautifully and evocatively written by Bruce Stewart, set out Timeslip’s stall with admirable clarity and real imagination and ambition. WEOT borrows from the “children on holiday get into scrapes” formula used in literary fiction by the likes of Enid Blyton and CS Lewis and plundered by kids’ serials from the 1960s and beyond. It throws us into its mystery in the opening sequence when a young bewildered-looking girl wanders across scrubland – an abandoned and forbidding-looking tumbledown block of buildings behind her – and disappears into thin air.

At the nearby village inn the Skinner family are on holiday. Frank (Derek Benfield), Jean (Iris Russell) and their daughter Liz (Cheryl Burfield) have been joined by teenager Simon Randall (Spencer Banks).

Immediately the show layers its mysteries. Also staying at the inn is the urbane Commander Traynor (Denis Quilley) whose presence is, at this point, unexplained. We learn that Frank was stationed at St Oswald early in the Second World War at the now-derelict naval base nearby but was invalided away due to an incident of which he has no memory. Out near the old station Liz and Simon encounter some sort of invisible, shimmering electronic force field…and when Liz discovers a “gap” in it she crawls through and disappears, followed swiftly by Simon.

The pair find themselves in darkness on the other side of a wire fence surrounding the now-operating research station. Captured and bundled inside, Liz and Simon encounter its commanding officer – a younger Mr Traynor from their hotel – and a fresh-faced rating who

introduces himself as Frank Skinner (John Alkin). Slowly Liz and Simon realise that they are in 1940 and that Liz has met her own father, years before she was born. Then the German raiding party arrives…

What’s especially fascinating about Timeslip is that “the time barrier” as it becomes known isn’t just a Narnia-like magic portal to another world; and it’s not a wonderful piece of alien technology that just happens to be able to wander through Time just because it does, like

What’s especially fascinating about Timeslip is that “the time barrier” as it becomes known isn’t just a Narnia-like magic portal to another world; and it’s not a wonderful piece of alien technology that just happens to be able to wander through Time just because it does, like

Doctor Who’s TARDIS. The presence of ITV’s “science expert” Peter Fairley at the beginning of episode one (and again at the beginning of the second story) is a sign that this series is going to offer a rationale for its use of time travel to drive the narrative. Commander Traynor in 1970 is at St Oswald for his own reasons which go back to the events of 1940.

It’s Traynor, a physicist, who offers up the fascinating and rather eerie idea that certain “sensitive” children (the show offers up, like the later Tomorrow People, the tantalising prospect of children being able to do things that adults can’t) can register and react to energy emissions created by traumatic events and experience those events as if they were happening again. Admittedly the science becomes muddier as the episodes progress; Traynor suggests that Liz and Simon are “hallucinating” the past; that they’re not really there so they can’t be injured.

Later, the idea of “the time bubble” is introduced, explained by Fairley in his introduction to episode seven as “a balloon…supposing some little patch of history gets slowed down…backwards and forwards it floats, as if it’s in a bubble.”

It’s then suggested that it might be possible to “get into that bubble – that bubble of history – and travel with it. Then you could move backwards and forwards in time at will…” It’s this uncertainty about how Liz and Simon – and village girl Sarah in the first episode – move through time that gives the series its sense of mystery.

For viewers in 1970 the sight of Liz and Simon fumbling for the invisible barrier (no-one who saw the series can ever forget that disturbing, jarring electronic ambience that signified its presence) before disappearing through it via a simple but hugely-effective split screen effect was thrilling and evocative. It was far more exciting than the thought of trying to rationalise the process through science, cod or otherwise.

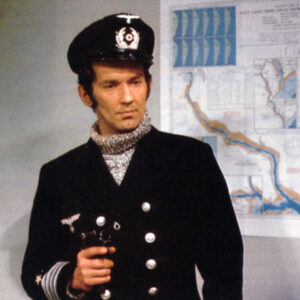

If Liz and Simon’s captures and escapes which thread through the serial are good old-fashioned adventure, WEOT really excels in scenes where 1940 Traynor and Gottfried (Sandor Eles), the leader of the Germans trying to find out what is really being researched at the station, are just sitting and chatting in Traynor’s requisitioned office.

This is adult drama, presenting two men from opposing sides in a war neither of them wants, discussing not only the nature of their own involvement, but also navigating their way around each other as men of science and intelligence. Gottfried is accompanied by his handful of “thugs” but he’s anxious to appear a rational, civilised man to Traynor. Traynor can see through it but clearly there’s more to Gottfried than a man on a mission; he wants to do what he can to bring the war to a swift conclusion with as few fatalities as possible.

This is adult drama, presenting two men from opposing sides in a war neither of them wants, discussing not only the nature of their own involvement, but also navigating their way around each other as men of science and intelligence. Gottfried is accompanied by his handful of “thugs” but he’s anxious to appear a rational, civilised man to Traynor. Traynor can see through it but clearly there’s more to Gottfried than a man on a mission; he wants to do what he can to bring the war to a swift conclusion with as few fatalities as possible.

The scenes between Quilley and Eles are electric, the former especially clearly relishing delivering his powerful, considered dialogue with a fruity, almost theatrical relish. Traynor in wartime is a man of ferocious principles, perhaps in contrast to the rather more devious and self-serving Traynor in 1970 who needs to resolve a mystery from 1940 (at any cost) as much as the bemused Frank Skinner does.

Liz and Simon become driven by different imperatives too. Once they have acclimatised to the fact that they have somehow travelled back in Time, Simon becomes part of Traynor’s mission to keep the station’s secrets away from the invaders; and Liz becomes set on finding out what caused her father’s injury.

There’s a sense of both characters maturing that carries on throughout the rest of the series’ long run.

WEOT is a masterful piece of television that stands up remarkably well. It’s pacy, full of incident and its scripts are intelligent and, most importantly, uncondescending to their intended audience. It’s full-blooded drama dealing starkly with an important era of history, underscoring it with a malleable and fascinating scientific concept that puts flesh on the bones of a trope too often used with little more than a magical flick of the wrist.

It also delivers, in the final moments of its sixth and last episode, an ice-cold and unexpected cliffhanger as Liz and Simon shuffle through the time barrier and leave 1940.

In a glorious pre-internet era when viewers didn’t know what was going to happen next or even how long a series was going to run, this cliffhanger was enough of a shock to cause viewers to fall off their sofas in surprise.

Trust me, I can vouch for this.